Destination Gestation

Graduate Studio Project at Princeton UniversityProject team: Rennie Jones, Abby Stone

Instructor: Andrés Jaque

Published in Lunch Journal vol. 11: Domestication in Summer 2016.

Human reproduction has long played an important role in shaping the design of the built environment, particularly through the figure of the idealized single-family home. Housing has been designed to sustain particular configurations of human relationships, augment human potential, and even to fundamentally alter the human psyche. Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky designed the Frankfurt Kitchen in direct relation to the human body, selecting and arranging elements to maximize human efficiency relative to food production and materializing a particular understanding of familial growth and operation.1 Henry van de Velde contended that domestic architecture should be designed to cultivate a child’s visual sensibility even while the fetus remained in the womb.2 Buckminster Fuller proposed the Dymaxion House as a stream-lined machine for sustainable living, intentionally calibrated to suit the human body as it functioned within the re-imagined family unit.3 At the level of regional infrastructure and configuration, the mass production of detached suburban housing in the United States in the mid-twentieth century was evidence of the popular appeal of the image of the iconic nuclear family, and continues to influence the way humans interact in contemporary society.

As the nature of procreation transforms today - through widespread fertility treatments, egg and sperm donation, in-vitro fertilization, and surrogacy - so too are urban and suburban conditions evolving. As women are increasingly delaying pregnancy and as growing numbers of homosexual couples seek to have children, demand for assisted reproduction has increased dramatically.4 The emergence of an international surrogacy market has begun to alter urban infrastructures and produce new architectural typologies, challenging the established notion of the family and the dwelling unit. Due to the high cost of surrogacy in the United States, American Intended Parents (IPs) have begun to look to developing nations for cheaper options.5

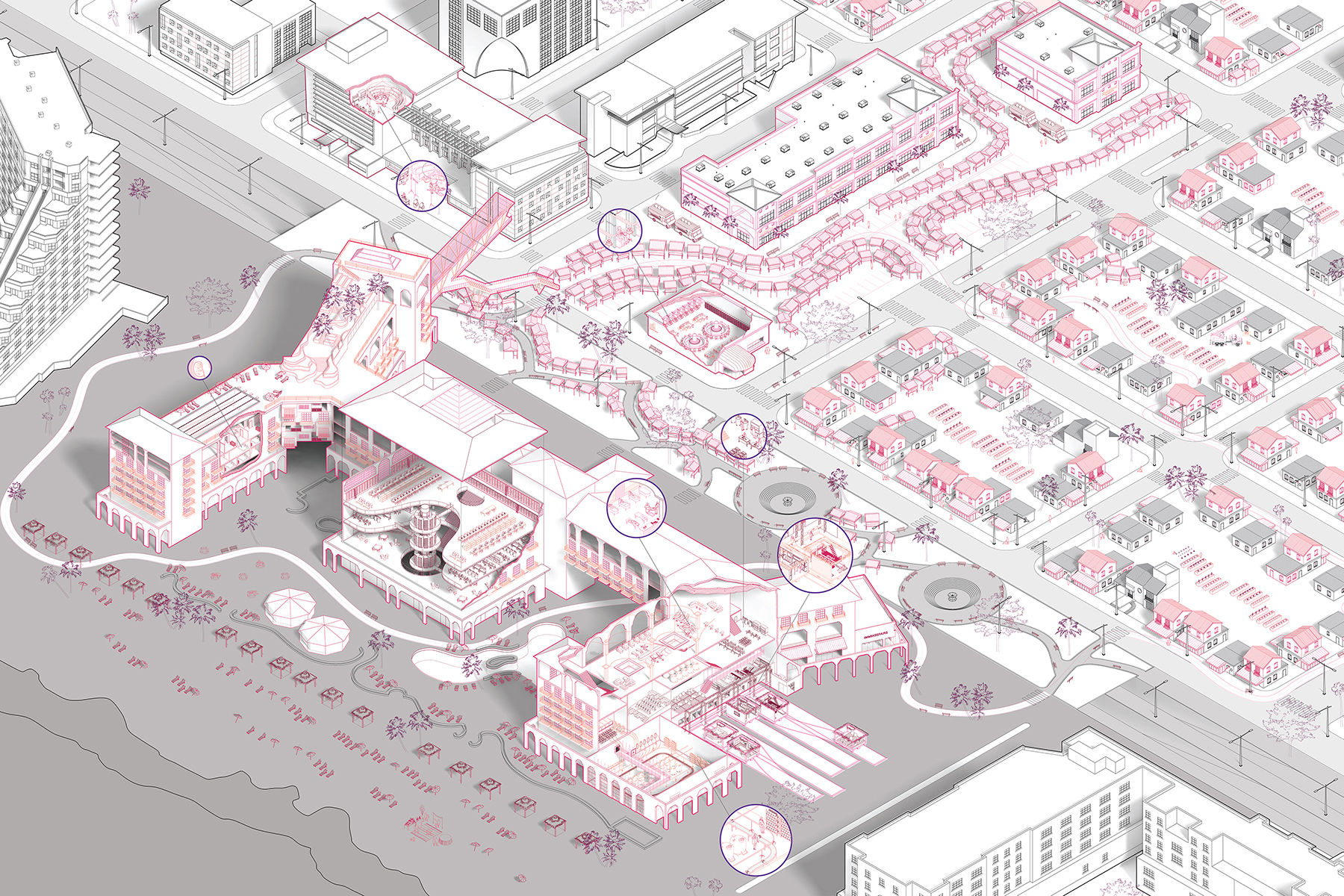

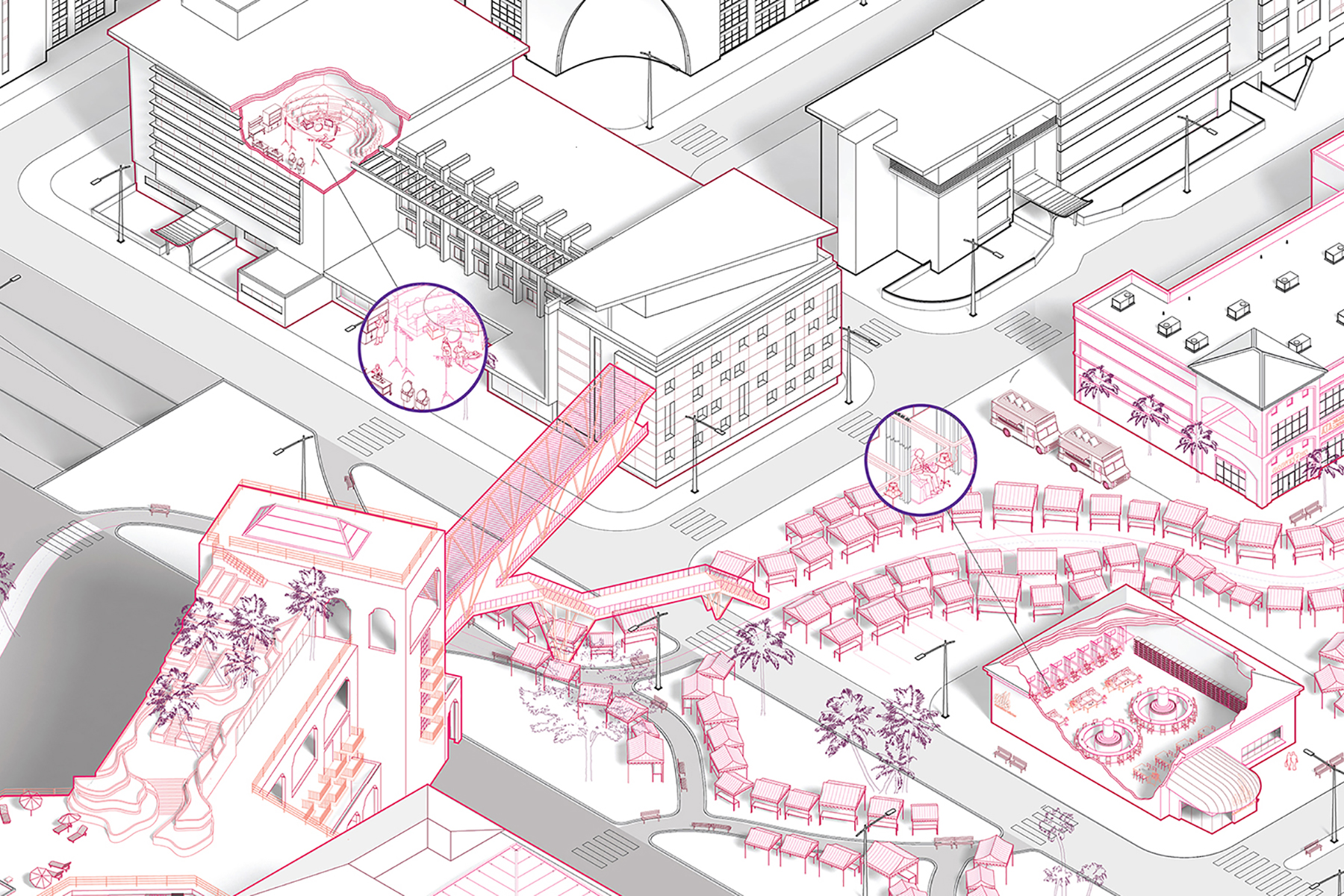

In Cancun, Mexico, a set of interrelated housing and medical building typologies specific to the human procreation market have begun to grow around the transportation infrastructure that makes them possible. Architectural devices have developed alongside medical and shipping technologies to form a system capable of designing, sustaining, and transporting the idealized human. The international surrogacy industry shapes environments at multiple scales, in order to modulate the human that this system produces. Specialized clinics and surrogate dormitories are designed as mechanisms to regulate the interior microenvironment in which the highly selected genetic material is to develop- that is, the body of the surrogate woman, constructed as an idealized, temporary machine for living in. Residents of the United States can browse the internet to select genetic material on sites that resemble online dating profiles, and often pay more for egg donors with Ivy League degrees or particular skin types.6 Due to advances in cryogenic storage and shipping, this genetic material might be selected in California from a donor in Russia and shipped to Mexico, for instance, where a surrogate would carry the desired baby to term. This process selectively privileges access to information, allowing those with purchasing power to choose and monitor genetic donors and surrogates through an international agency without revealing their identities to the other members of this technologically-extended family. Often, the surrogacy agencies that connect Mexican surrogates in Cancun to intended parents in the United States offer all-inclusive resort and fertility packages to the IPs, pairing in vitro with a day at the beach, thereby extending the IPs a measure of control over their own health and wellness.

The dislocation of reproduction afforded by this system of surrogacy beyond borders stretches the notion of family across international boundaries and biological relations, challenging the traditional notion of parenthood and the figure of the single-family home. This new family is housed in a complex, interrelated system of architectural typologies, urban infrastructures, genetic storage facilities, and bodies, decentralizing the family unit at a global scale. As genetic material can be cryogenically frozen to be stored indefinitely, and potentially donated to other IPs, these systems also dislocate the family across time, challenging conventional notions of nearness implied by ‘nuclear.’

Destination Gestation imagines a tongue-in-cheek, hypothetical future for international surrogacy spawning from an existing surrogacy resort in Cancun, Mexico. The drawing depicts an accelerated version of the complex networks necessary to sustain this machine for family production, pressurizing some of the inherent tensions to reveal potential absurdities. The Destination Gestation resort houses an immense loading dock for cryogenic shipping and a multi-level library for cryogenic storage of genetic material, which could potentially house millions of future familial components in genetic data. A masturbatorium with street-front shop windows and themed rooms reveals the centrality of the genetic material market and incorporates this market into the resort typology. Other elements seek to extend the potential for human modulation beyond the body. Resident surrogates might study medicine or nursing while waiting for their own check-up at the clinic, or spend their nine months of intensive ‘rest’ in surrogacy homes creating products for sale in the town market. Fertility-related businesses pop up in the district, such as a “Milk Bar” in which babies can sample a range of breast milk options and surrogates may chose to work as paid wet nurses after they give birth. The suburban typology that surrounds the resort complex suggests that surrogates may stay near the site, perhaps welcoming back the children they gave birth to, or using the money earned during the gestation period to modify the home to function as a small business. The surrogacy industry remains a highly controversial topic, overlapping with many of the ethical and legal debates surrounding outsourcing, wage inequality, and medical tourism. The issue sometimes draws a fine line between empowerment and exploitation.7 As the international surrogacy market continues to grow, the first step toward imagining a situation in which each member of this extended nuclear family benefits mutually and at an equal scale may be merely to compress the disparate networks that support the system into one frame, thereby making this new international domestic sprawl as visible as its suburban counterpart of the twentieth century.

Notes

1. Kinchin, Juliet, and Aidan O’Connor. Counter Space: Design And The Modern Kitchen. The Museum of Modern Art, 2011.

2. Shand, P. Morton. “Henry van de Velde. Extracts from his Memoirs: 18911901.” The Architectural Review112:669 (1952): 143155. This observation should be credited to Spyros Papapetros of Princeton University.

3. Fuller, R. Buckminster, and Jaime Snyder. Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth. Carbondale : Southern Illinois University Press, 1969.

Fig. 2. OBGYN health center incorporates an operating theater where surrogates can receive medical attention and learn medical skills during their extended stay. The Milk Bar provides a social environment for nursing and a marketplace and tasting bar for pumped breast milk.

4. Boggs, Will. “Assisted Reproduction Rates Increasing Worldwide.” Reuters.4 June 2009.

5. Grether, Nicole. “Going Global For A Family: Why International Surrogacy Is Booming.” Aljazeera America.12 May 2014.

6. Jones, Ashby. “Putting a Price on a Human Egg.”Wall Street Journal. 26 July 2015.

7. Gerber, Paula, and Katie O’Byrne, eds. Surrogacy, Law and Human Rights. Farnham, Surrey, England and Burlington, Vermont: Ashgate, 2015.